Donna Porterfield:

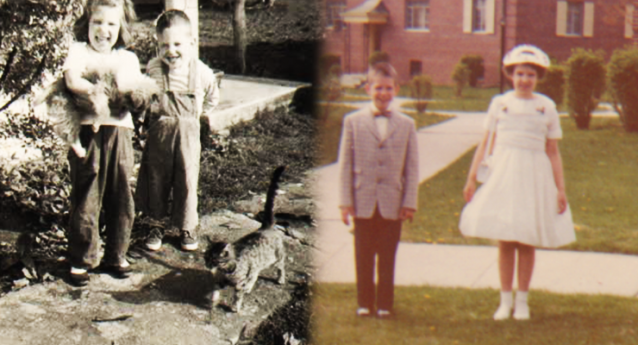

As an adult, I discovered that my parents, my brother, and I each remembered in detail the events of one particular year – the year we moved from a small farm in Berkeley County, West Virginia to a two-bedroom, third floor apartment in the Washington, D.C. suburbs of Fairfax, Virginia.

For me, at age nine, the move was both upsetting and exciting. It was exciting coming from a four-room school to a sprawling brick school with a shiny cafeteria and a library with more books than I’d ever seen in my life. My new teacher was a good one – smart and kind. When she saw that kids were making fun of me because of my “hillbilly accent,” she read us Tom Sawyer at our after-lunch rest period, introducing the class to the concept of dialect. And, she chose me to be the Class Library Assistant, which meant I could go for one hour a week and work in the school library. I was elated.

Most weekends, we travelled back to West Virginia. We stayed at my maternal Grandma’s house, where my brother and I spent a lot of time up in her cherry tree (me on the lower branches, he at the tippy top). We were surrounded by aunts and uncles, cousins, and neighbors, all of whom could tell us kids what to do and give us down the road if we didn’t do it. We were encircled by love and nature, and still too young to be responsible for the hard work and living the adults took on. At age ten, Fairfax, Virginia was exciting, but Berkeley County, West Virginia was paradise.

Once, after spending the day at the Porterfield farm with my father’s mother and his brother’s six daughters, my cousin Ellen and I wandered down the lane toward the barn. I looked out over the field of wheat in the evening light, and it took my breath away. I convinced Ellen to climb up on the fence with me and sing “America the Beautiful,” all the verses, with particular emphasis on “Oh beautiful for spacious skies, for amber waves of grain.”

Moments of paradise can be experienced, but paradise itself doesn’t live permanently in any place I’ve been. The making of a close, loving family doesn’t depend on living in the country. Every community, rural or urban, has it assets and liabilities, and we make of it what we must. For me, living in a rural community where most everyone knew everyone else – and everyone else’s business -- taught me to accept people for who they are, because even if I didn’t like them, didn’t agree with them, I could depend on them for help when help was needed. One day recently, I was looking at my brother’s Facebook page and noticed he, too, had listed his home town as Martinsburg, West Virginia, despite all the many places we have lived.

Savannah Barrett:

This past June, I attended the Americans for the Arts annual conference where I listened in on a creative placemaking panel. The panel was all urban, and early in the discussion my friend and mentor Judi Jennings raised her hand to ask that we recognize the lack of rural representation. The moderator responded sincerely by asking the audience to raise their hand if they lived or worked in a rural community. Although I recognized his question to the group as an effort towards inclusivity, I felt that his framing of that question lacked nuance. I was surprised to feel so personally affected, and in that moment began to recognize something important in my view of rural: I realized that although I could raise my hand at this moment in my life, when my work with Art of the Rural stations me in rural communities as often as my urban Kentucky apartment, there had been many instances when I wouldn’t have been represented in that question.

In that moment, I was reminded that many of us who identify culturally as rural don’t live and work in rural places, but are still among the most passionate advocates for rural communities. Not because we live or work in rural areas, but because we have a deep connection to a rural place, and because that rural place belongs to us, and is sometimes, even if not all of the time, where we belong.

That sense of belonging, of ownership, is hard to come by for my generation. We’re more fluid, less tied down, more transient than any generation before us. I’m grateful to have inherited that sense of belonging, and the one place that I consistently belong has been along the hills, fields, homes and creeks of my family’s homeplace in Grayson Springs, Kentucky.

The homeplace has been in my family for seven generations. I was raised up there alongside the entirety of my extended family: My great-grandparents, grandparents, my Memaw’s siblings, one great aunt, one family of second cousins, all of my aunts and uncles, all of my first cousins, and my family have lived on this land during my lifetime. The land is sacred to me. It is the physical place that roots me to the people I love most, and to some aspects of my personality that I most value.

As a child my mother took me to my great-great grandparents’ house, by then abandoned and home to the visitations of livestock and woodland creatures. She walked me across the creek while telling me about the swinging walking bridge that used to hang along the path, to show me the poetry she and her first love had written on the wallpaper. I’ve hiked to this homeplace with my Memaw, with great-aunts, with my own younger brother and sister. The house seemed to me the bearer of our history. I swam in front of the house as a child, and picked blackberries in the fields above it. I know the stories from this home so well that when I imagine them, I conjure the oppressive heat always present when I’ve visited, and I smell the water in the air from nearby Lizard Creek.

I left this land in 2004 to attend college at the University of Louisville. I was the first person in my family to go away to college, and remain the only member of my extended family to live further than seven miles from the homeplace. Although I returned on a sometimes weekly basis until moving to attend the University of Oregon, it was moving away from this place that revealed its overwhelming role in my life. My sense of culture is almost entirely gleaned from experiences I have had on this land, and because I have been a witness to so many people’s life and death on this property, I sometimes feel that my family’s lifeblood is literally contained in the dirt and water of that acreage.

The material artifacts of my ancestors have always fascinated me. I carried boards from that homeplace with me to Oregon to be comforted by the place that is the vessel of my spirit, and to remember the people that connect me to it in perpetuity. I’m proud of my little piece of rural America, and although I’ll likely move in and out of it over the course of my life, I know that it will always be the place that is mine, and, in one way or another, the place that I am.