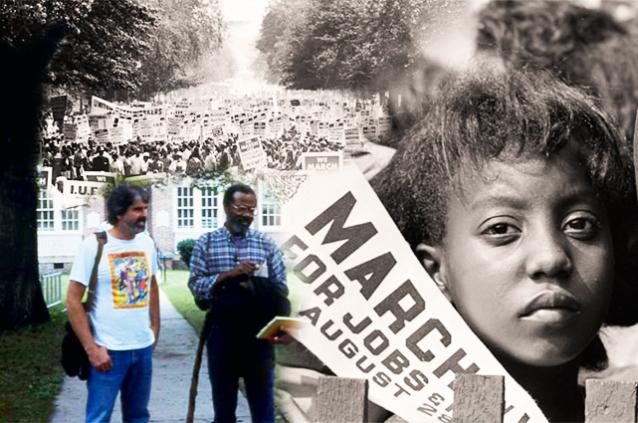

Fifty years ago this month, a quarter of a million people from across the United States peacefully marched on Washington D.C. for jobs and freedom. It was the biggest civil rights rally in the nation’s history, marked by M. L. King Jr.’s speech, "I Have a Dream." The next year Congress passed into law the 1964 Civil Rights Act , followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1963, I was 17 years old. I’d been raised in Princess Anne County, Virginia beside the ocean, in the woods and soybean fields, and on the bays fishing, hunting, and trapping.

We didn’t have a TV, but I can still feel some of the sinking feeling when I got the news that Medgar Evers had been killed by a white man hiding in the bushes across from his house in Jackson, Mississippi. It felt like the hope for our country had suddenly just drained away.

Two years later, Malcolm X was assassinated in Harlem by three black members of the Nation of Islam, which he had quit and repudiated for its own brand of racial supremacy. When he was a little boy, Malcolm X’s father had been killed, likely by white supremacists, and at least one of his uncles had been lynched.

Like King and many others, I came to view the civil rights movement as encompassing an equal need for struggle in the northern city as well as the southern county; as including poor whites as well as poor people of color; as taking a stand on Viet Nam, which was signaling the country’s entry into a new era of rich man’s war -- poor man’s fight.

As 1967 turned into 1968, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were planning a late spring occupation of Washington. The Poor People’s Campaign would join the issues of race, place, class, and war under one banner. After King himself was assassinated on April 4th by another white man, this time hiding in a building across from the Memphis hotel where King was spending the night, the Poor People’s Campaign never regained momentum. Robert Kennedy, attempting to pick up King’s fallen mantle, would be assassinated two months later by Sirhan Sirhan.

In 1976, I moved to the central Appalachian coalfields to use theater, documentary film, and audio recording to support what was demonstrably going to be a lifetime of struggle. That’s when I met John O’Neal, co-founder of the Free Southern Theater – the theater wing of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee/SNCC:

I met Dudley in ’76, Sarasota, as I recall. I was on this mission to find out what was going on with these white people organizing, what was their organizing impulse? I saw Red Fox/Second Hangin’— the show these Roadside guys had brought to the Sarasota ROOTS performance festival. The play is about the impact of coal mining and industrialization on Southern Appalachia, the impact on the culture and the people, built up out of oral histories and research. I was impressed by the performance. The simultaneous grounding in the culture and the focus on an important issue, using the culture as an avenue to approach it -- that was interesting.

The Roadside gang was the only company at the ROOTS festival to go have beers, get out guitars, and sing after everything was closed down for the day. So I thought, these are my kind of people. Now this was before the surgical repair of Dudley’s bad eye, and he tended to focus with his one good eye and hold you intently with a gaze. He said, “John, what did you think of our little play?” Now Myles Horton at Highlander had told me that Roadside was performing for poor and working class white people in Southern Appalachia, and near Knoxville, Tennessee is where the KKK was founded. So I said, “From what I understand about what y’all are doing, you have a lot of potential Klansmen in your audience, and, frankly, I didn’t see anything in your play that would make a potential Klansman less likely to be a Klansman then before he listened to your story.”

Now I had some experience working with white people, and I knew that this kind of aggressive, though polite response had a tendency to push them up against the wall. And I liked to get them there and place needles in them, and hold them like specimens to see what they would do. Dudley, he didn’t miss a beat, said, “Hmm. What do you think we ought to do about that, John?” Now I came there not planning on doing shit. I came to keep an eye on what the white people were doing. That’s what started the work that Dudley and I continue to this day, in one way or another. Memory is a tricky thing, but that’s how I think it went down.

_________

Editor’s note:

John and Dudley (pictured above) were co-founders of Alternate ROOTS and went on to co-create and tour nationally (and occasionally internationally) new plays, to found the American Festival Project, and to argue with anyone who would listen about the critical role art might play in achieving universal human rights.

Dudley is the artistic director of Roadside - [email protected]

John and Dudley invite you to join them in New Orleans, October 17-20, for a gathering of activists, educators, and artists to celebrate and carry forward the 50 year legacy of Free Southern Theater.

_________

Dialogue from our Facebook page:

Harry Boyte - "I had a similar experience -- in fact was assigned by MLK to organize poor whites, which I did for most of seven years among millworkers in Durham, a profound life shaping experience. I also learned from the movement - especially Rustin -- that we need a large strategic frame of "winning over the broad middle," many more than 50 percent (the great Mississippi movement leader Thelma Craig said that for any truly radical change one needs to aim for 80%). So, I believe we have to have a broad strategic challenge to the substitution of what Bayard Rustin called the "moralist" strategy for serious politics of building people's power."

Jamie Haft - "Harry, Dudley, and others: How important are organizations to "winning over the broad middle" and "building people's power" as part of an effective movement for social justice? I'm trying to understand the role of Imagining America, as an organization, in meeting its mission of transforming higher education so that it fulfills its public role in our democracy. I find skepticism among my activist peers under 30 years of age about the efficacy of building institutions."

Dudley Cocke - "Building nonprofit grassroots institutions is currently out of fashion, rationalized by calls for entrepreneurship and abetted by a national over-emphasis on the individual. How many genius awards are given to cooperatives? None that I know of, and it's intentional. For those who study power, the subtext is clear: It's OK for there to be many small organizations and radical individuals (and grassroots umbrella organizations trickling down unsubstantial amounts of money to them), but keep the institutional power imbalance severely tilted to advancing the interests of a few over the many. It is understood that whatever dissent occurs below the institutional level is manageable, even useful, as it functions as a safety valve for the majority's frustration and anger, and a handy mechanism for co-option. In the 1960s and '70s the civil rights movement inspired a number of grassroots leaders to begin the difficult task of building community-based cultural and arts institutions -- Inner-City Arts in Los Angeles, the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio, Appalshop in Appalachia, Caribbean Cultural Center (CCCADI) in New York, to name a few. Beginning with the election of Ronald Reagan, the pressure on them to fail has been unrelenting, with the result that such institutions have either shut down, changed their social justice mission, or, at best, now find themselves punched out, hanging on the ropes. Without strong grassroots institutions, it will be near-impossible to achieve the broad-based movement Harry Boyte rightly calls for."

Harry Boyte - "This question goes directly to the issue of "where to organize?" I think you've identified a key problem, Jamie -- the reluctance of young adults to get involved in "organization building." The related question is how to reconstruct and democratize many other organizations -- schools, health clinics, small businesses, congregations, colleges, even government agencies, among others. The narrow map of where to organize -- the "voluntary" or "community" sector is the dominant map -- takes most places of power and potential people's power off the map.

An additional note, Jamie. Rustin, who was so insistent on winning the broad middle, made a strong point about the need for what he called "institutional reconstruction," based on his experiences especially organizing in the 1930s and 1940s, when democratic change agents had a much wider sense of where to organize -- offices, the media, government, universities, schools, churches, businesses, all were conceived as organizing sites.

Here's Rustin's quote, from his great essay From Protest to Politics, challenging the "moralist" faction, making the point. WHen he says elsewhere in the essay that the movement needs to build "community centers of power" this is clearly what he is getting at:"Sharing with many moderates a recognition of the magnitude of the obstacles to freedom, spokesmen for this tendency survey the American scene and find no forces prepared to move toward radical solutions. From this they conclude that the only viable strategy is shock; above all, the hypocrisy of white liberals must be exposed. These spokesmen are often described as the radicals of the movement, but they are really its moralists. They seek to change white hearts—by traumatizing them. Frequently abetted by white self-flagellants, they may gleefully applaud (though not really agreeing with) Malcolm X because, while they admit he has no program, they think he can frighten white people into doing the right thing. To believe this, of course, you must be convinced, even if unconsciously, that at the core of the white man's heart lies a buried affection for Negroes—a proposition one may be permitted to doubt. But in any case, hearts are not relevant to the issue; neither racial affinities nor racial hostilities are rooted there. It is institutions-social, political, and economic institutions—which are the ultimate molders of collective sentiments. Let these institutions be reconstructed today, and let the ineluctable gradualism of history govern the formation of a new psychology."

Jamie Haft - "Thanks, Harry and Dudley, for pointing out that a number of grassroots civil rights activists in the 1960s and 1970s saw building new institutional bases of power as the next logical step to advancing (and sustaining) the movement. Inspired by the Black Arts Movement, some of these activists started community-based arts and culture nonprofits working at the intersection of social justice. From my research on these voices from the cultural battlefront, I recognize the founders' impulse to institutionalize the movement’s values - inclusion, distributive leadership, cooperative decision-making, and critical discourse. Building organizations isn't glamorous, but I agree with Rustin that change past a point won't occur and be sustained without such nitty-gritty efforts. Are enough of us in my generation clear about the need to build grassroots organizations of sufficient scale to sit at the tables of power? Those of us born after 1980 have been raised to the drumbeat of getting government, especially the federal government, off our backs - and it’s a short step from there to dismissing institutions as agents of change. I hope you each will look for more and wider opportunities to continue intergenerational conversations such as this one."

Harry Boyte - "Jamie -- this is a very important thread to discuss across generations, especially for the larger "civic agency politics" (a politics of civic empowerment) that I am convinced represents the next stage of the movement. We're in Vermont this weekend, and I had a long conversation with two young people in Washington, both scientists very interested in "civic science" - one on a congressional staff the other in NIH They say their whole cohort in DC is really searching for a larger politics and vision -- the specific issue fights, while important, simply don't add up to a sense of where we're going."

Beegie Adair - "Dudley, that's a beautiful piece. It brought back a lot of memories, good and bad, for me, from that period. The black jazz musicians here in Nashville were discouraged from working with the white guys (and girls), and we all had to find places to play that would not cause a ruckus. I was playing a gig at Belle Meade Country Club the night M. L. King was killed. When I got in my car, the news was on the radio, and I drove home in shock. I felt bereft, and Nashville instantly put a curfew in place, and there were armed soldiers in tanks at 25th and West End Avenue, in front of Centennial Park. That was as close to being in a war zone as any of us had ever been. I was so radicalized by that time, after the Birmingham Church bombings and the three civil rights workers in Mississippi, that I was ready to go out and do something, just anything, to make myself feel better. The curfew and the tanks lasted about 5 days. 1968 remains in my memory as the worst year I can remember. I began to think the civil rights movement, and the women's issues, and the Vietnam issues were a part of the whole picture. I think that is accurate. It was all about the 'haves', and the 'have nots'. I'm sorry to say I think the current climate is helping those issues come back again, like an old ghost."

Note: Beegie Adair is a Nashville Jazz Musician/Steinway Artist. Check out her beautiful piano playing in one of her original compositions for the musical Betsy.